PHP Basics: PHP Beginner Tutorial

PHP is one of the most common scripting languages on the web, powering everything from small personal sites to some of the largest content platforms. It began in the mid-1990s and is still popular today because it’s easy to start with and runs almost anywhere. Being open source means you can install it freely, explore the code, and take advantage of a large ecosystem of extensions, frameworks, and hosting options.

When you’re just starting out, it helps to understand the basics: what PHP stands for, what a PHP file actually is, and how PHP works inside a server. From there, you’ll see how to open a PHP file in an editor, how to run one on your own machine with the built-in server, and how to use the configuration file php.ini to control settings. These fundamentals form the foundation for writing and testing your own scripts.

As you get hands-on, you’ll also want to practice with everyday file operations. PHP makes it straightforward to check whether a file exists, upload user files, delete old ones, and even serve downloads safely. Along the way, we’ll cover examples that illustrate each step, so you can not only see what a PHP file example looks like but also try running it yourself on localhost.

Why PHP is the Best for Web Development

PHP remains a dominant force in web development because it checks so many practical boxes at once. It’s open source, easy to deploy, and available on nearly every hosting platform by default—so you can get a site running with minimal configuration. According to W3Techs, PHP powers around 74—76% of all websites whose server-side language is known (ZenRows). That level of adoption means almost any shared hosting, cloud provider, or LAMP‑stack tutorial will work out of the box.

It integrates seamlessly with popular databases like MySQL, and content management systems (CMSs) such as WordPress and Drupal are built in PHP—making it easy to customize or extend them. For example, WordPress alone powers over 40% of all websites, so learning how PHP files work immediately gives you leverage over a massive portion of the web (techjury.net, en.wikipedia.org).

Long-term, PHP’s resilience comes down to its ecosystem: a vast body of tutorials, libraries, hosting environments, and community tools (like Composer and Packagist) that make development faster and more reliable. This pragmatic clarity—where you can code, deploy, and scale without reinventing the wheel—is a big reason why PHP is best for web development in many real-world scenarios.

According to ZenRows:

“PHP is the Programming Language of Choice for 18.2% of Developers”

PHP Compared to Other Backend Options

| Feature / Factor | PHP | Node.js (JavaScript) | Python (Django/Flask) | Ruby (Rails) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Share | ~74–76% of websites with known server-side tech (W3Techs) | ~2% (W3Techs) | ~2% (W3Techs) | <1% (W3Techs) |

| Hosting Support | Almost universal (shared, VPS, cloud, LAMP stack by default) | Requires Node-compatible hosting, more setup | Widely available, but less ubiquitous than PHP | Limited outside specialized hosts |

| Learning Curve | Easy to start (embed in HTML, simple syntax) | Easy if you already know JS, async concepts required | Gentle syntax, but frameworks add complexity | Beginner-friendly but opinionated framework |

| Framework Ecosystem | Laravel, Symfony, WordPress, Drupal, Magento | Express, NestJS, Next.js (server-side) | Django, Flask, FastAPI | Ruby on Rails |

| Use Cases | Content-driven sites, e-commerce, blogs, APIs, rapid prototyping | Real-time apps, SPAs with frontend JS, APIs | Data-heavy apps, APIs, scientific web tools | Startups, rapid prototyping, convention-over-config |

What PHP Stands For & What It Means

It started as “Personal Home Page,” later backronymed to “PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor.” The modern reading captures the core idea: it preprocesses server-side logic to generate the final response that the browser sees. Instead of shipping raw .php files to a client, the interpreter executes your code on the server and returns HTML, JSON, or another format. This model keeps secrets (like database credentials) on the server and lets you build pages that adapt to users, sessions, and data.

What PHP Can Do

It renders dynamic pages, handles forms, talks to databases, emits JSON for single-page apps, runs command-line utilities, and automates everyday file tasks. With extensions you can resize images, queue background jobs, and call external services. Popular frameworks (Laravel, Symfony) add structure, but you can start with a single file and scale up as features grow. Because it’s good at templating and request/response flows, it works well for classic server-rendered sites and as a fast API layer.

What Are PHP Files

They’re plain-text scripts processed by the interpreter. The server never sends the raw source to the browser; it executes the code and emits output. You can mix markup and logic in the same document—just wrap code in <?php ... ?> blocks. The interpreter evaluates those blocks linearly, so it’s common to compute data at the top, then render it inside the page layout. This split of “compute then present” keeps pages simple while still enabling dynamic content.

What Is The PHP File Extension

Use .php for executable scripts. You might see legacy setups using other extensions or server-specific mappings, but the conventional choice helps editors and tooling recognize syntax and security rules. If you need to store support files that shouldn’t be executable (like templates or configs), consider keeping them outside the public document root or naming them clearly to avoid accidental exposure.

PHP File Example

Here’s a tiny script that mixes markup and logic:

<?php

$greeting = "Hello";

$name = "World";

?>

<!doctype html>

<html>

<body>

<h1><?= htmlspecialchars("$greeting, $name!") ?></h1>

</body>

</html>This shows the common pattern: compute variables first, then embed them inside markup. The htmlspecialchars() call avoids injecting raw characters into the page, which is a safe default whenever you print user-controlled data.

How To Open A PHP File

Open it in a text editor (VS Code, PhpStorm, Vim). Syntax highlighting and language servers catch mistakes early. Double-clicking won’t “run” it like a desktop app; the right approach is either the command-line interpreter or serving it with a web server. If you’re exploring someone else’s project, skim the entry points (often public/index.php) and configuration files to see how routing is wired up.

How To Run A PHP File

Run a script directly from the command line:

php path/to/script.phpFor web output, place your files where the web server expects them and route traffic to an entry script. Many modern apps use a single front controller (e.g., public/index.php) that loads dependencies and dispatches requests to controllers. When you’re experimenting, it’s often quicker to use the built-in server:

php -S localhost:8000 -t publicThat command serves the public directory and routes requests there, which is perfect for testing small sites without editing full server configs.

How To Run A PHP File On Localhost

The built-in server is the fastest path to a working page during development:

cd public

php -S localhost:8000Visit http://localhost:8000 and iterate. This mode is single-process and not meant for production, but it mirrors enough of a real environment to validate routing, sessions, and basic database access. When you’re ready for more realistic behavior (multiple workers, process management), switch to Nginx or Apache with PHP-FPM and reuse the same code.

How Does PHP Work

For web requests, the server hands control to the interpreter through an interface (module, FastCGI, or FPM). The interpreter runs your script, calls extensions for things like database queries or image processing, and streams the response back. On the command line, the same interpreter executes the file in a process with no web server involved. This dual nature—CLI and web—makes it handy for scheduled jobs and one-off utilities as well as full applications.

Where The php.ini File Lives

You can find the php.ini file by getting your active configuration paths:

php --iniOr in code:

<?php phpinfo(); ?>Security Note:

phpinfo()is useful during local development, but DO NOT leave it exposed on a production server. It reveals detailed configuration data that could help an attacker.

There are separate configs for the CLI and for FPM/Apache, so editing one may not affect the other. Typical locations include /etc/php/*/cli/php.ini, /etc/php/*/fpm/php.ini, or the installation directory on Windows. Some hosts also honor .user.ini files in project directories for per-site overrides, which is useful when you can’t edit system-level settings.

Disable PHP Warnings

During development, show everything and fix it; in production, log errors and avoid exposing details to users. You can set this at runtime:

<?php

error_reporting(E_ALL & ~E_NOTICE);

ini_set('display_errors', '0'); // off in productionPrefer server or php.ini settings for consistency, then restart the service. Also configure where logs go (file path or syslog) so you can trace issues after they happen without revealing internals in the browser.

Check If A File Exists

Use file_exists() to test presence, and prefer is_file() when you specifically need regular files rather than directories:

<?php

if (file_exists('/path/to/report.pdf')) {

// proceed

} else {

// handle missing file

}When working with user-supplied paths, normalize with realpath() and verify the target lives under an allowed directory to avoid path traversal. Reading content is straightforward once the path is validated:

<?php

if (file_exists($p)) {

$data = file_get_contents($p);

}Upload A File

Always validate size, type, and destination. Minimal example:

<?php

if ($_SERVER['REQUEST_METHOD'] === 'POST' && isset($_FILES['upload'])) {

$tmp = $_FILES['upload']['tmp_name'];

$name = basename($_FILES['upload']['name']);

$dest = __DIR__ . "/uploads/$name";

if (is_uploaded_file($tmp) && move_uploaded_file($tmp, $dest)) {

echo "Uploaded.";

} else {

http_response_code(400);

echo "Upload failed.";

}

}HTML form:

<form method="post" enctype="multipart/form-data">

<input type="file" name="upload" />

<button>Upload</button>

</form>Watch upload_max_filesize and post_max_size in configuration, and keep the upload directory outside the public document root or restrict direct access. If you later serve these files, sanitize names and mime types to avoid unintended execution.

<?php

$ok = is_uploaded_file($_FILES['f']['tmp_name'])

&& move_uploaded_file($_FILES['f']['tmp_name'], __DIR__."/uploads/".basename($_FILES['f']['name']));PHP: Delete A File

Confirm the target and guard the path before removal:

<?php

$path = __DIR__ . '/uploads/example.txt';

if (is_file($path)) {

unlink($path);

}For extra safety, compare real paths and ensure the file lives under the intended directory:

<?php

if (is_file($p) && str_starts_with(realpath($p), realpath(__DIR__.'/uploads'))) {

unlink($p);

}Consider logging deletions or moving items to a trash folder in user-facing apps, which makes recovery easier if someone clicks the wrong button.

Download Files

Serve downloads with the right headers and a safe path:

<?php

$path = __DIR__ . '/files/manual.pdf';

if (!is_file($path)) { http_response_code(404); exit; }

header('Content-Type: application/pdf');

header('Content-Length: ' . filesize($path));

header('Content-Disposition: attachment; filename="manual.pdf"');

readfile($path);For a generic download where the type varies, use an octet-stream header and still validate the path:

<?php

header('Content-Type: application/octet-stream');

header('Content-Disposition: attachment; filename="file.bin"');

readfile($path);On high-traffic servers, offload large transfers to the web server using features like X-Sendfile or internal redirects, which reduces memory pressure in application code.

What PHP Version Am I Using

From the command line:

php -vIn code:

<?php echo phpversion();Version checks are handy for enabling optional features or choosing polyfills. You can also inspect PHP_VERSION_ID for an integer comparison in conditional blocks, which keeps compatibility decisions explicit in your codebase.

TL;DR

Hello World

<?php echo "Hello, World!\n";Localhost Quick Start

php -S localhost:8000File Check

<?php if (file_exists($p)) { /* handle */ }Version

php -vPHP Code Examples

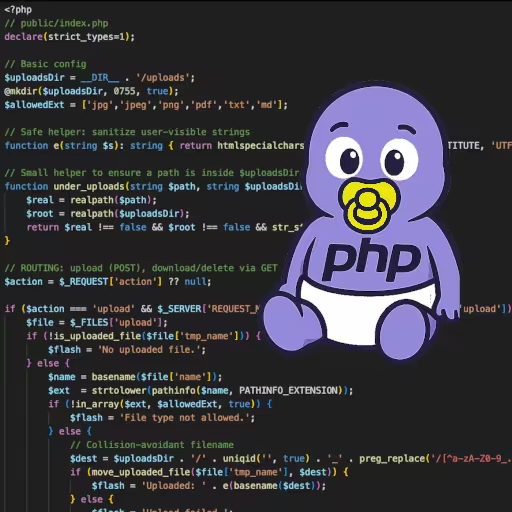

Below is a compact, usable index.php you can drop into a public/ folder and run with php -S localhost:8000. It demonstrates the core bits mentioned in this article (including safe output with htmlspecialchars(), checking file_exists(), upload handling, delete, and a basic download handler):

<?php

// public/index.php

declare(strict_types=1);

// Basic config

$uploadsDir = __DIR__ . '/uploads';

@mkdir($uploadsDir, 0755, true);

$allowedExt = ['jpg','jpeg','png','pdf','txt','md'];

// Safe helper: sanitize user-visible strings

function e(string $s): string { return htmlspecialchars($s, ENT_QUOTES | ENT_SUBSTITUTE, 'UTF-8'); }

// Small helper to ensure a path is inside $uploadsDir

function under_uploads(string $path, string $uploadsDir): bool {

$real = realpath($path);

$root = realpath($uploadsDir);

return $real !== false && $root !== false && str_starts_with($real, $root);

}

// ROUTING: upload (POST), download/delete via GET action

$action = $_REQUEST['action'] ?? null;

if ($action === 'upload' && $_SERVER['REQUEST_METHOD'] === 'POST' && isset($_FILES['upload'])) {

$file = $_FILES['upload'];

if (!is_uploaded_file($file['tmp_name'])) {

$flash = 'No uploaded file.';

} else {

$name = basename($file['name']);

$ext = strtolower(pathinfo($name, PATHINFO_EXTENSION));

if (!in_array($ext, $allowedExt, true)) {

$flash = 'File type not allowed.';

} else {

// Collision-avoidant filename

$dest = $uploadsDir . '/' . uniqid('', true) . '_' . preg_replace('/[^a-zA-Z0-9_.-]/', '_', $name);

if (move_uploaded_file($file['tmp_name'], $dest)) {

$flash = 'Uploaded: ' . e(basename($dest));

} else {

$flash = 'Upload failed.';

}

}

}

header('Location: ./'); exit;

}

if ($action === 'download' && isset($_GET['file'])) {

$file = $uploadsDir . '/' . basename($_GET['file']);

if (!is_file($file) || !under_uploads($file, $uploadsDir)) {

http_response_code(404); echo "Not found"; exit;

}

// Serve as attachment (simple)

header('Content-Type: application/octet-stream');

header('Content-Length: ' . filesize($file));

header('Content-Disposition: attachment; filename="' . e(basename($file)) . '"');

readfile($file);

exit;

}

if ($action === 'delete' && isset($_GET['file'])) {

$file = $uploadsDir . '/' . basename($_GET['file']);

if (is_file($file) && under_uploads($file, $uploadsDir)) {

unlink($file);

$flash = 'Deleted: ' . e(basename($file));

} else {

$flash = 'File not found or forbidden.';

}

header('Location: ./'); exit;

}

// Simple page rendering

$files = array_values(array_filter(scandir($uploadsDir), function($f) use ($uploadsDir) {

return is_file($uploadsDir . '/' . $f);

}));

?>

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>PHP Basics — demo</title>

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width,initial-scale=1" />

<style>

body{font-family:system-ui,Segoe UI,Roboto,Helvetica,Arial;max-width:760px;margin:2rem auto;padding:0 1rem}

.box{border:1px solid #ddd;padding:1rem;border-radius:6px}

.muted{color:#666;font-size:.9rem}

table{width:100%;border-collapse:collapse}

td,th{padding:.4rem;border-bottom:1px solid #eee}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>PHP Basics — small example</h1>

<p class="muted">PHP version: <strong><?= e(phpversion()) ?></strong></p>

<section class="box">

<h2>Upload a file</h2>

<form method="post" enctype="multipart/form-data" action="?action=upload">

<input type="file" name="upload" required>

<button type="submit">Upload</button>

</form>

<p class="muted">Allowed extensions: <?= e(implode(', ', $allowedExt)) ?></p>

</section>

<section style="margin-top:1rem" class="box">

<h2>Uploaded files</h2>

<?php if (count($files) === 0): ?>

<p class="muted">No uploaded files yet.</p>

<?php else: ?>

<table>

<thead><tr><th>File</th><th>Size</th><th>Actions</th></tr></thead>

<tbody>

<?php foreach ($files as $f): $path = $uploadsDir . '/' . $f; ?>

<tr>

<td><?= e($f) ?></td>

<td><?= e(number_format(filesize($path))) ?> bytes</td>

<td>

<a href="?action=download&file=<?= rawurlencode($f) ?>">Download</a>

—

<a href="?action=delete&file=<?= rawurlencode($f) ?>" onclick="return confirm('Delete <?= e($f) ?>?')">Delete</a>

</td>

</tr>

<?php endforeach; ?>

</tbody>

</table>

<?php endif; ?>

</section>

<section style="margin-top:1rem" class="box">

<h2>Quick examples from the article</h2>

<pre><code>// Check if a file exists

$p = __DIR__ . '/uploads/somefile.txt';

if (file_exists($p)) { /* handle */ }

// Simple "Hello World"

echo "Hello, World!\n";

// Show phpinfo() — useful for dev only

// <?php // phpinfo(); // run locally, do NOT expose in production ?></code></pre>

</section>

<footer style="margin-top:1rem" class="muted">

<p>Note: this demo is intentionally small. For production, add authentication, CSRF protection, stricter MIME checks, quotas and virus scanning.</p>

</footer>

</body>

</html>WARNING: The above code is NOT for production—remove in-production debug bits, add auth, CSRF, better MIME checks, quotas, and virus scanning.

Conclusion

You’ve seen what the language is, how it runs, where configuration lives, and how to handle everyday tasks like uploads, downloads, and file checks. Start with the built-in server to iterate quickly, keep configuration differences between CLI and web in mind, and default to safe patterns such as escaping output and validating paths. With those basics in place, you can expand into routing, database layers, and background jobs while reusing the same interpreter for both web requests and command-line utilities.